Rise and Fall of the Tongs

Contents

When we think about Chinese organized crime in the United States, it usually goes paired with the presence of ‘tongs’: secret societies or brotherhoods that offer their members employment opportunities, aid to start up businesses and generally make life easier for Chinese migrant workers to settle at their destination. They would also make it possible to make the journey across.

In the west we came to picture tongs as superstitious secret brotherhoods consisting of hordes of topless Chinese gangsters with dragon tattoos fighting it off in the alleys of Chinatown in Kung Fu-style fights. While there is some truth in this, because street gangs would often recruit from Kung Fu schools in the 1980’s, tongs are much more than rebellious teenagers seeking glory. In fact, they’re one of the many political byproducts of a multidimensional super nation in Eastern Asia, of which westerners rarely know a lot about its history. A reflection of China’s paternal culture predating Chinese Communism. A country with a long arm that had a great historical influence on the nations surrounding it, but also a country with age-old internal turmoil.

Let me take you on a journey throughout the history of Chinese in the United States, the harsh conditions under which they resided and were targeted by racists and the conditions under which the tongs were able to flourish and eventually collapse.

© Hong Kong, Hong Kong Maritime Museum, The Dragon and the Eagle: American Traders in China, A Century of Trade from 1784 to 1900, Dec. 2019-April 2019, no.5.14 (one from the set of ten).

© Hong Kong, Hong Kong Maritime Museum, The Dragon and the Eagle: American Traders in China, A Century of Trade from 1784 to 1900, Dec. 2019-April 2019, no.5.14 (one from the set of ten).The Taiping Rebellion was a massive civil war between syncretic Christians and the Qing dynasty which resulted in a pyrrhic victory for the Qing. The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was led by Hong Xiuquan who was the self-proclaimed brother of Jesus.

The Taiping Rebellion: The Bloodiest Civil War

In the mid 19th century, China was economically quite weak and culturally divided. British imperialism was still prevalent and religious fringe groups such as the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom caused on-going turmoil, resulting in the massive Tai Ping Rebellion: a decade long conflict between syncretic Christians and China’s Manchu government.

In the United States, the “yellow influx” led to the establishment of the two most notable Chinese-American enclaves: San Francisco Chinatown on the West Coast and New York Chinatown on the East Coast. With the vast majority of the Chinese population in the United States practically being in California. “Yellow labor” was a derogatory term used to refer to the “cheap” Chinese labor migrants that moved to the United States and worked on the transcontinental railroad and during the earlier gold rush.

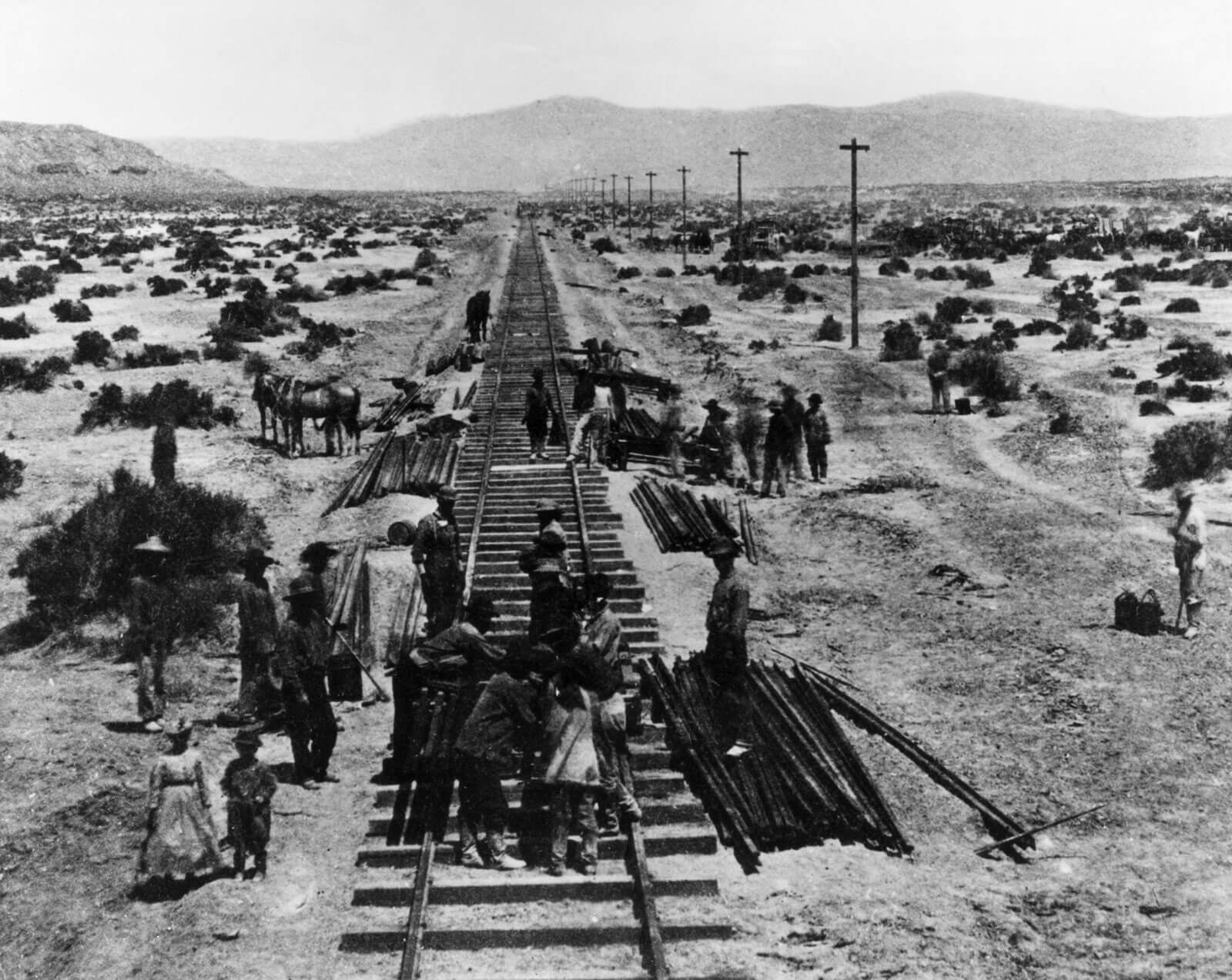

© Hulton Archive

© Hulton ArchiveWorkers laying tracks for the Central Pacific Railroad in Nevada, 1868.

The Transcontinental Railroad

In 1862 the US federal government – motivated by the “Manifest Destiny” – signed the Pacific Railroad Act. Giving the mandate for a grand, ridiculous project that came to be considered the greatest technological feat of the 19th century: a transcontinental railroad between the East Coast and the West Coast that would be built at speed through hostile Native American territory and through harsh, unforgiving environments.

Two railroad companies would start a race from each side of the United States to construct the Transcontinental railroad, racing to the rendez-vous at the halfway-point in Promontory, Utah. The project allowed for additional territorial expansion, was key to enabling the Wild West, the flourishing of trade and the Native American genocide.

The project was pestered by disaster. Workers were demotivated, drunkards and were violent among each other. When they had enough money, they would leave to participate in the Gold Rush. The construction project was also defined by overcoming problematic natural barriers such as the Rocky Mountains and frequent guerilla attacks by Native Americans in tribe territory.

© Amon Carter Museum of American Art Archives, Fort Worth, TX

© Amon Carter Museum of American Art Archives, Fort Worth, TXGing Cui, Wong Fook, and Lee Shao, three of the eight Chinese workers who put the last rail in place, on a float at the 50th Anniversary celebration of the completion of the transcontinental railroad in Ogden, Utah.

The American Dream & The Yellow Peril

The problem of labor was eventually solved by contracting a Chinese workforce. Afterwards, nine out of ten workers were Chinese. Others Irish. The Chinese had nothing to lose, with abysmal wages being far higher than they could ever imagine in China. And the risk of death and disease were worth it to find fortune. They were shipped from China by the hundreds, seeking to make money to send to their families overseas.

The journey to the land of opportunity was an expensive venture the Chinese often couldn’t pay for out of their own pockets. In the 1850’s, opportunistic merchant organizations were set up to ease the move to the United States and make it more appealing. Workers would be facilitated in their move to the west by Chinese merchants, but would then often have to pay off unrealistic financial debts. But the wages in the west were often higher even after taxes than in China.

This situation was an important time for the establishment of tongs. The need for financial assistance and mass migration served as an incubator for tongs fueled by the Chinese’s paternal ideology. The tongs took care of the sick and elderly and shipped corpses back to China for burial.

In 1870, China was ruled by the Manchurian Qing Dynasty which had been reigning the country since 1636.

In 1870, China was ruled by the Manchurian Qing Dynasty which had been reigning the country since 1636.

Anti-Manchurianism and the Han Chinese

The first tong in the United States – the Chee Kong Tong – was formed by a former leader in the Tai Ping Rebellion before the rebellion was crushed in 1864. And more interestingly, the founder of the Chinese Republic – Sun Yat-Sen – was inspired by this tong’s anti-Manchurian ideology during his three-month stay in the United States at the age of eighteen. The Chee Kong Tong, otherwise known as the “Hung Society”: a fraternity of Ming-loyalists or former secretive religious folk sect. The Chee Kong Tong was one of the primary supporters of Sun Yat-Sen during his revolutionary efforts in 1912.

Many Tongs were semi-political organizations with anti-Manchurian sentiments because at the time China had been ruled for hundreds of years by a Qing emperor – a dynasty with its roots in northern Manchuria. An increase of nationalistic efforts by the Qing government in the early 19th century, sparked Manchurians to more strongly identify with their cultural roots. In turn, this caused Ming-loyalists to identify more strongly with anti-Manchurianism, which empowered political forces in China that traditionally longed for the reestablishment of a Ming emperor.

Most migrants came from the southern provinces in and around Guangzhou, explaining why the spoken language in Chinatowns is Cantonese instead of Mandarin – the language spoken in the majority of China. The majority of Chinese migrant workers came from Cantonese-speaking provinces.

Image of people smoking opium in Beijing in 1932.

Image of people smoking opium in Beijing in 1932.Throughout the 1800s, China was strongly dependent on opioids as a currency, going as far as to levy an opioid tax in the country. In San Francisco, opioid dens were widespread.

Chinese Ghettos and The Opioid Crisis

The Chinese consolidated in Chinese ghettos. Workers shared bunk beds around the clock. When one finished sleeping, the bed would be passed off to somebody else. Often in claustrophobic spaces with astronomically high rents.

The vast majority of Chinese laborers were men and this proved to be problematic. Whatever women came – often considered too meek to work in the tough labor conditions of the pacific railroad – would work in sweatshops. Some entered into prostitution, a profession the Chinese invented long ago. But the point remains that Chinese men in the United States had nobody to sate their desires or provide entertainment. The tongs thrived on gambling and prostitution, activities illegal by law in the United States, but deeply ingrained in Chinese culture.

The tongs funded their benevolent activities with an underground economy. Therefore, tongs would often ship women to the United States, sometimes slave-girls. Either to work at brothels prevalent in the Chinatowns, or they would be married to Chinese men overseas.

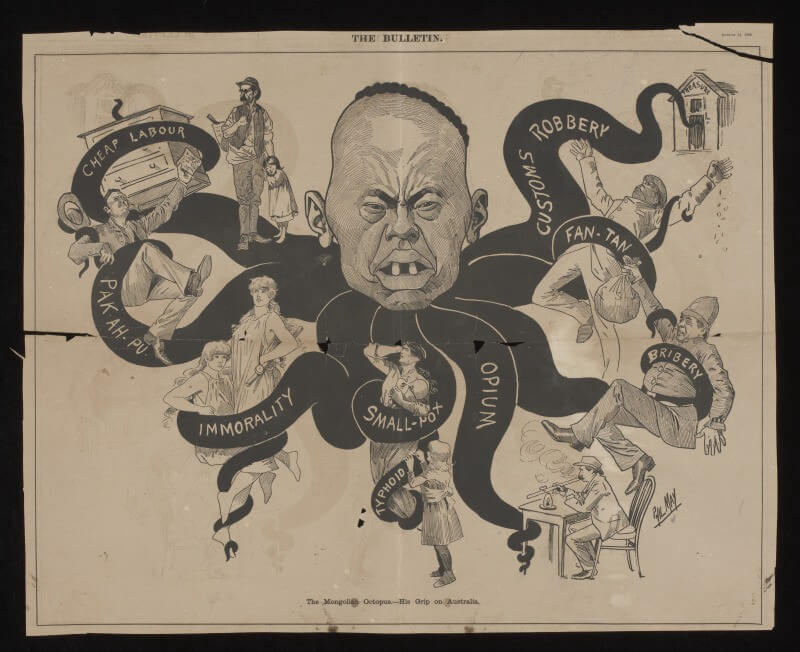

This contributed to further anti-Chinese attitudes as stereotypes arose of Chinese enclaves where men would visit brothels, smoke tobacco and gamble. And an estimated 50% of China was severely addicted to opioids. Some intellectuals argued that allowing Chinese workers into the country lowered the cultural and moral standards of American society. The Chinese laborers who often worked in worse conditions and were ready to do more for less, were prickly thorns for the Irish and Latino communities that also moved or lived in the land of opportunity. Especially after the transcontinental railroad had finished and Chinese workers sought out other sources of income.

Chinese workers moved into the farming industry and did factory work – particularly in the garment industry. As a token of gratitude, the Chinese workers faced harsh repression from the Caucasian community who were ready to take their jobs. They were considered the “yellow peril” and America was better off without them, motivated by western superiority.

Institutionalized racism

When the Chinese had success in their own right, some rising to become entrepreneurs themselves, anti-Chinese sentiment was on the rise throughout the entire 19th century. A financial depression during the 1870’s was the last straw, and the United States government continued to pass legislations that limited future immigration of Chinese workers.

Legislation exempted Chinese workers from constitutional rights, made it hard to migrate to the United States and legislatively pushed Chinese out of the laundry and garment business. Chinese workers faced harsh bigotry and racism, being forced out of some of their communities by rioting mobs that set Chinese ghettos ablaze. In 1873, the Queue Ordinance made police cut off many Chinese’s “Queue” – long braids and shaved foreheads as was tradition with the Manchurians. Under Qing rule, in the 17th century Han Chinese men were forced to adopt the Manchu hairstyle. Chinese workers were also forced to live separated from their families and forced Chinese workers into separated communities in which they would fend for themselves (Chinatowns).

One of the first legislations culminated in Chinese businesses requiring special licenses to set up shop in the United States or preventing Chinese from naturalization. And eventually, the United States made Chinese immigration impossible. To top it off, a later act prohibited reentry into the United States after visiting China. Moving into the next century, after extending the act twice, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended indefinitely – a legislation prohibiting Chinese workers from migrating to the United States.

© The National Museum of Australia, “The Mongolian Octopuss”, The Bulletin, 31 January 1880

© The National Museum of Australia, “The Mongolian Octopuss”, The Bulletin, 31 January 1880Chinese were a political scapegoat blamed for many problems in the country. In the above propaganda cartoon, they are depicted as a menace.

In San Francisco, Anti-Asian attitudes resulted in an Anti-Asian movement in the 1860s and 1870s. Before that, San Francisco was a relatively peaceful city with low crime rates. This also counted for Chinatown. However, Anti-Asian groups organised, ready to push the Chinese over and take their jobs. They marched to demand the expulsion of the Chinese from American soil because they thought that the Chinese were being used as cheap labor alternatives. They would vandalize Chinese-run facilities in San Francisco Chinatown.

In the 1870’s Anti-Asian sentiments further intensified. False rumors of leprosy and smallpox outbreaks in the Chinese communities. In 1871, approximately 20 Chinese workers were hanged by a lynch mob of 500 white and hispanics following the death of a policeman at the hands of a Chinese. Politicians opportunistically joined the show to pluck the fruits, forming outright Anti-Asian parties. They took particular offense to the high rate of prostitution in Chinatown caused by the disproportionate amount of young, Chinese males. The tongs used the social dilemma to make an immense amount of money through prostitution.

'Kongsi'

Pre-1911 revolutionary Chinese society was distinctively collectivist and composed of close networks of extended families, unions, clan associations and guilds, where people had a duty to protect and help one another. Soon after the first Chinese had settled in San Francisco, respectable Chinese merchants—the most prominent members of the Chinese community of the time—made the first efforts to form social and welfare organizations (Chinese: "Kongsi") to help immigrants to relocate others from their native towns, socialize, receive monetary aid and raise their voices in community affairs. At first, these organizations only provided interpretation, lodgings and job finding services for newcomers.

The Six Companies was a paternal coalition representing Chinese in California run by the higher educated immigrant population.

The Six Companies was a paternal coalition representing Chinese in California run by the higher educated immigrant population.

The Six Companies

The first Chinese merchants' association was formed in 1849. Within a few years it was succesvilly replaced by Chinese district and clan associations because more immigrants came in greater numbers. Eventually some of the more prominent district associations merged to become the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (more commonly known as the "Chinese Six Companies" because of the original six founding associations). It quickly became the most powerful and politically vocal organization to represent the Chinese not only in San Francisco but in the whole of California.

The Six Companies, a paternal coalition representing all Chinese in California ran by the higher educated immigrant population, tried to quell the movements. But preoccupied with fighting Anti-Asian sentiment, this opened the floodgates for criminal

Witch Hunt

The collapse of the Six Companies, the organization fighting against bigotry and corruption, was caused by numerous factors. One was that as they were preoccupied with Anti-Asian sentiments, they allowed the tongs to further organize. If one tong would shed themselves of unwelcome members, they would go on to form a new group and on and so forth.

By the end of the 19th century, there were hundreds of tongs. Then, the Six Companies booked some progress in fighting the tongs, but were thwarted by other stakeholders. The tongs namely profited off of prostitution rackets. The Six Companies continuously chose the diplomatic route, seeking to work with the American institutions to quell tong influence. For instance, they managed to coerce the American government in passing several legislations that would make it possible to extradite Chinese brides back to China, as well as the criminal boo how doy. But this was often thwarted by Caucasians who had interests in the Chinese Red Light Districts.

But the Six Companies were often falsely blamed for defects in the Chinese communities, as the organization was shrouded in mystery to outsiders. They were, for example, accused of being in control of the criminal tongs. Really, the Six Companies were on an active witchhunt and would chase the tongs to the end of the world to quell the criminal elements in Chinatown.

The Tong Wars are notorious for bloody back alley and rooftop fights between rival gangs in which guns and various types of blades and hatchets were used as weapons. One individual could be part of as much as five tongs at the same time.

The Tong Wars are notorious for bloody back alley and rooftop fights between rival gangs in which guns and various types of blades and hatchets were used as weapons. One individual could be part of as much as five tongs at the same time.

The Tong Wars

The greatest contributing factor to the collapse of the Six Companies, in turn giving free rein to the tongs, was maybe American ignorance and – instead of fighting the tongs – their on-going efforts to thwart the Six Companies. The final straw was when congress took away the Six Companies’ absolute power: the exit visa tax. The exit visa tax was a receipt that proved workers had repaid all their debts and they could go home. Without it, the Six Companies had no leverage over any of the Chinese, including its criminal elements.

The eventual collapse came about during the first extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The Six Companies gave opposition by calling upon all Chinese to protest it and donate to employ lawyers. But while the protest was to no avail, the American government accused the Six Companies of setting up the Chinese population against America and stimulating them to violate the law. The Six Companies lost face to the Chinese, and the tongs opportunistically put a prize on the Chinese protest leader’s head. Immediately afterwards, a full-scale war between the criminal elements in Chinatown broke out in the streets of Chinatown.

This guerilla war between the tongs came to be known as the Tongs Wars. They fought in the streets, in the alleys and on rooftops. The fights ensued over the limited amount of women, defamation of the tongs or over business ownership. Chinatown was far too small for the hundreds of tongs that existed. The Six Companies had prevented earlier wars for the last fifty years via hard repression, bounties and boycotts. But now that the Six Companies was checkmate, it was happy hour for the hundreds of street gangs that had built up over the years and the vat exploded with a bang. The boo how doy would attack one another with hatchets and flail each other’s skin in particularly bloody ways. To make things worse, tongs had often already split up, causing some members to be part of up to five tongs at the same time. The tongs would go on to fight over soldiers, but no single tong ever reigned supreme.

© Photograph by Arnold Genthe. Copyright Corbis.

© Photograph by Arnold Genthe. Copyright Corbis.After the San Francisco earthquake, little was left. An estimated 3,000 people died of the 14,000 inhabitants. Anti-Asian movements grabbed the opportunity to attempt to relocate Chinatown to Telegraph Hill, but to no avail. Afraid to lose the lucrative oriental trade, and ironically restricted by their own legislations that prohibited Chinese Americans from relocating, Chinatown was rebuilt.

The Fall of the Tongs

The last blow to the Six Companies was a boycott of products which grounded the economy of the whole Quarter. Several attempts were made to ease the tension but with little success. The fighting was encouraged so that the different fraternities would remain weak.

After half of the Chinese population had left Chinatown, the Tong Wars ultimately ended not because one tong reigned supreme– not because of a negotiated peace treaty– not because the police interfered. The Tong Wars were ended by the interference of the one and only Mother Nature. In 1906, the earth violently shook during the San Francisco earthquake and not much was left of the Chinese Quarter, so there was little to fight over. Subsequent fires had destroyed the ghettos, gambling halls and brothels. This was the death knell for the warring tongs, as many of their staple sources of income never were able to come back.

Most tongs just simply went away with the old Chinatown. Some of the boo how doy simply “grew too old”. Others moved away to other American cities. An exceptional group kept up the Tong Wars in New York City and Chicago for another twenty years, but they also succumbed eventually. Afterwards, legislation was passed to end the overflow of brothels and opium dens. In San Francisco, the police forced the last six tongs among which the Hop Sing Tong and Suey Sing Tong to establish a peace committee and things quieted down with the last tong-related murder being in 1921.